The funeral tea-party was nearly over - if indeed such an elegant collation of smoked salmon, caviar and canapés, mille-feuilles, passion fruit pavlova and a sculpted ice swan could properly be described as a mere tea-party. Katerina Ivanova leaned against the wall and pondered upon the ceremony and the demeanour of her hostess. She had enjoyed neither.

The silver and black edged invitation had bidden her to attend the “Golden Sunset Crematorium (Private) to join with us in a Secular Ceremony of Farewell to Anna Yanovskaya Smith, widow of John and dearly beloved Mother of Jules (formerly Ulyana)..... Light refreshments in the Hospitality Suite.....R.S.V.P. Mrs Peregrine Cavendish-Brown....”

Katerina took the bus from the tube station to the Godalming Road. She hitched up her long black silk skirt which she had for many years always worn at funerals, and sometimes at weddings too, and strolled back up the road towards the massive wrought iron gates and the wide gravel drive which welcomed the better class of mourner who usually attended Golden Sunset ceremonies. She glared at the Jags and the Mercs and the Porsches in the car park but smiled at the old tandem bedecked with black ribbons padlocked to the railing beside the portico. At least someone, she thought, in this maelstrom of conspicuous wealth and

over-consumption has contrived to get their priorities right.

A flunkey directed her to the Secular Suite. She pushed open the silver and black door and found an empty room awash with purple brocade and black silk, velvet and plush, silver and crystal and preposterously large flowers. In a gloomy corner on a purple bier, almost swamped by a huge wreath of lilies, stood an elaborate black coffin. Secular-ceremonial the room might be designed to be, Katerina mused, but it seemed to her to be awfully like a shrine to bad taste.

Other mourners began to arrive and she retired to a far corner and composed herself for the Ceremony. One word from the Director, a spotty faced young man with pebble glasses and a peculiarly unctuous voice, and she retreated into private consciousness and memory. She and Anna Mikhailovna Yanovskaya had been brought up together in Paris. Anna’s grandfather, banker and astute businessman, had in 1904 moved the family money from St Petersburg to Switzerland and his import-export business and his young family to Paris away from the burgeoning threat of revolution. The Paris business had prospered and the boxes of gold in the Swiss bank had multiplied. Katerina’s own father, the impoverished Count Ivan Gretchaninov, had fled in 1917 also to Paris away from the mayhem that was now loosed in Russia to the shelter and support of the old banker’s son with whom he had gone to school in St Petersburg. The Count and Countess lived happily enough until the Countess’ death in April 1921 two days after the birth of her second child Nikolai Ivanov. The Count never recovered from this loss, never accepted the new baby, took no consolation from the company of his amazingly beautiful three year old daughter Katerina and just after daybreak on a soft July morning in the Bois de Boulogne blew his brains out with the revolver he had brought with him from Russia. His old school friend and his wife opened their hearts and their home to the two orphans and brought them up to be sister and brother to their own one year old daughter Anna.

The young man had stopped talking and music was piped in - sentimental, little children in smocks talking to the bunny rabbits in a woodland glade sort of music. Katerina in her mind’s ear began to sing the sad slow Contakion for the Departed. When, blessedly, the piped music stopped and the chat began again she returned to her memories.

Although Katya was the eldest of the three, it was Anna with her plain happy face and untroubled conscience who mothered and managed the trio, who soothed their hurts and was proud of their many accomplishments. Nikolai was a studious boy with a precocious talent for drawing and painting. Katya was a fine musician with a lovely singing voice which as she matured grew rich and deep. In 1936 the ever perspicacious Mikhail Yanovsky moved his émigré family and household away from Paris to Lausanne where Katya studied at the Conservatoire while Nikolai attended the Ecole des Beaux Arts in Geneva. In 1946 as the concert halls of Europe reopened, Katerina embarked upon a highly successful singing career and Nikolai began to buy and sell fine pictures.

Anna’s son-in-law read a poem of dubious literary merit to which Katerina listened politely, but she returned to memory when yet more regrettable music filled the Ceremony Room. The Yanovskys returned to Paris and Anna met and married John Smith, a young Englishman who had been appointed director of Mikhail’s business interests in London. They bought a big house in Surrey where eventually Anna had a fat and healthy baby girl baptised Ulyana, who grew into a plain and spoiled young woman, married a humourless merchant banker, tended to despise her gentle mother and wholeheatedly hated her mother’s outspoken friend Katerina. They met occasionally in the nursing home into which Anna, after John’s death, had been put as soon as her increasing frailty had become an inconvenience to Ulyana’s important social life. Six months after Anna’s removal Ulyana informed her mother that she had renounced all things Russian and was henceforth to be known as ‘Jules’. Anna, although unhappy, made no protest. Katerina, thoroughly impatient, did so very loudly. Jules shouted that Auntie Katya was an interfering old bat and could leave now. So the invitation to the Ceremony had come as a great surprise.

Suddenly everyone stood up. Pebble Glasses turned to the coffin, waved his hands in the air in what he probably thought was a dignified and meaningful manner and to the sound of muted trumpets the curtains behind the bier parted and the casket slid away into anonymous gloom. Katerina crossed herself three times, and said out loud “Everlasting be your memory, O our sister, who are worthy of blessedness and eternal memory. Come, all you her kindred and friends: now is come the hour of parting. Let us pray to the Lord to bring her to her rest.” Jules interupted her quietly genteel weeping and glared at Katerina. “My friends,” she said, “please do join Peregrine and myself for refreshment. Everyone,” a slight pause, “is most welcome.”

Katerina looked across the Hospitality Room at Jules. Her skirt was too short, her bodice too tight, she was drinking a great deal of champagne and in her high pitched laugh as she circulated amongst her friends was more of tears than of joy. Uneasy for a moment she watched Jules with a small parcel in her hand making her way with tiny bird like steps towards her.

“Aunt Kate. How nice of you to come.”

“Ulyana. How kind of you to invite me. And my name is Katya.”

“And mine Aunt Katya is Jules.”

Katerina heard both the anger and the appeal in the voice. She stretched out her hands, placed them on the young woman’s shoulders and said gently:

“Forgive me. I am old and changes are sometimes alarming. I’m truly pleased you asked me today. I would have been very sad if I hadn’t been able to say good-bye to Anna. Thank you.” She leaned over and kissed Jules lightly on both cheeks and turned to go.

“Wait a moment, please Aunt Katya. Mama asked me to give this to you. She said it had been precious to her, and that when she was gone she hoped it would be precious to you - a sort of treasure that she wanted to share with you.” She held out the small package.

“I’d love to have something of Anna’s. Whatever is it? “

“It’s just an old framed photograph of you and her, when you were girls in Switzerland. Anyhow, she made me promise that I would give it you. Please, do take it.”

“That was so thoughtful of your mother. The older I get the more important the old photos seem to be.” She took the parcel and put it into her deep black bag.

“And now, I think I really must get back to Pimlico. Goodbye my dear. God bless you. I will hold you in my heart.” She clasped the diamond and emerald encrusted hands for a moment, turned, and walked away.

Sometime later Katerina let herself into the apartment in Warwick Gardens which she and Nikolai had shared for many years. She went wearily up the stairs to the drawing room where her brother sat looking out at the gardens. He rose from his chair, taller than his sister but with the same mass of silver hair, strong features and bright mischievous eyes.

“Good evening Countess.” He kissed her hand.

“Good evening Count.” She made him the slightest of curtseys.

“How went your day?”

“In parts, dreadful. The place was dreadful, the Ceremony was dreadful, the music was very dreadful indeed. And I didn’t behave very well.”

“And the party?”

“All right, perhaps. The food was a bit over exuberant. But I made my peace with Ulyana. I left her with a smile and a blessing of a sort.”

“What’s that in your bag?”

“Oh, that. It’s a present - from Anna. A photo Ulyana said.”

“May I see?”

“Of course. But give me a drink first, and then you can open it.”

He filled a glass from the decanter on a side table, brought it over to her, took the parcel and very carefully removed the picture from its padded envelope.

“It’s a photo I took of you and Anna in Lausanne. Two lovely Russian girls, so happy, so full of life. It’s a pretty frame, silver-gilt, but the back is made of wood. That’s why it’s so heavy. Do you mind if I take a closer look at this?”

“Of course not. But do be careful with the photo. Anna said it was a treasure she’d wanted to share with me.”

Nikolai stroked the wood and weighed the picture in his hands. With a slim antique penknife he gently eased out the tiny pins which held the wooden back against the carved frame. Slowly, carefully he removed the panel, glanced at it, and handed it almost reverently to Katerina.

"I think this may be Anna's treasure." he said.

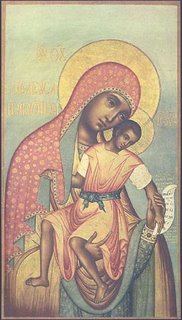

“Oh Kolya,” she said, “it’s an icon. The Virgin Eleousa, the gentle Mother. The colours, and the exquisite patterns on her robes, and the protecting curve of her body around the Christos. It’s beautiful. Is it original?”

“No. The original is much, much bigger. It's in the Tryakov Gallery in Moscow, painted by Simon Ushakov in 1668. This little panel here is just a copy of the original, but it’s exquisitely done and extraordinarily like Ushakov’s. Look. Look how young the virgin is, how her face is rounded and so much more human than in the old icons. It was the influence of Western European naturalistic painting on Ushakov and his School. An old agnostic person like me can empathise much better with this young loving mother in her pretty dress than with the old stylised stiff Virgins who say nothing to me at all. You know.....”

He glanced across at his sister and broke off. With a slight smile around her lips, Katerina had fallen asleep where she sat on the sofa. Very gently he took the icon from her hands and laid it on the table. ‘Stop lecturing and being such an old bore, Kolya.’ he said to himself. ‘But what a blessing Katya, this hidden treasure that Anna Mikhailovna has left to you. God be praised.'

Naomi